“If you always do what you always done, you’ll always get what you’re always got..!”

Roger Hallam PhD researcher, Kings College London. February 2015.

Email: organics2go@googlemail.com / radicalthinktank@gmail.com

Five minute Introduction..

This is my first stab at getting out into the real world and entering into a dialogue with activists in London about the ideas I have on the subject of effective political action. This being my first attempt to communicate my research it is necessarily going to be incomplete and I am still working out the best way to communicate – so apologies in advance for any lack of clarity. Inevitably then I will change things around as I talk to activists and learn from their experiences and taylor my research to become more grounded what is most effective at his time in this city. I am going to avoid academic language as much as possible so what I say can be hopefully be understood easily by any interested reader. And apologies for any typos on this first draft (not my strong point!)

So my pitch is that there are ways in which activists can become a lot more effective in their collective action – and arguable massively more effective. This is primarily by using their resources and the potential resources out there, in terms of people they try to get on their side, in a more effective way. It is then about working with what you have not about some ideal world where you have more power then you have in the here and now.

At the moment I have a collection of mechanism and processes which I have drawn from extensive research into the successful tactics and strategies used by civic resistance and radical campaigns from around the world over the past 50 years. The research aim is the find what works best and why – and how it can be applied here and now and particularly how the social media/internet can be used to make these mechanisms even more effective.

I will say a little bit about myself and then give a brief introduction the main idea I want to bring to the table as it were. So even if you have only 5 minutes you can read basically what I am proposing. Hopefully that will encourage you to read the rest of the text where I will go into greater details so you can fully appreciate the power of these ideas.

About myself. I have been involved in activism and various social movements for 30 years – since I was 15. I was active in the peace movement in the 80’s and went to prison several times for various direct actions. I worked with a civil rights group in India before getting a scholarship to study economics at the London School of Economics. I left after a year to set up a radical alternative university. To cut a long story short it evolved in the first national federation of radical housing co-ops and worker co-ops. I helped to design the participatory structures of this organisation and spent a good 15 years as a trainer and facilitator in various radical green/social alternative contexts. I have written booklets on how to setting up a housing co-op and anarchist economics. In more recent years I have set up several ethical businesses. During this time I have canvassed and/or spoken on the phone to over 25,000 people. I now live on an organic farm in Wales and come down to London in the week. As a result of the financial crisis and the new radical participatory potential of the internet/social media I have decided I better get back involved in political things and see what can get organised. So here I am! I am now doing a PhD on the design of digitally enhanced mechanisms of radical political mobilisation and empowerment.

The last point is the disclaimer: Nothing I am writing here is intended to promote illegal activities. How any reader uses this information for is outside my control and therefore I cannot be responsible for it.

A brief summary of a potentially explosive mechanism.

So here is a flavour of what I am here to communicate:

At present all round the world there are small group of people – academics, activists, social entrepreneurs, who are literally jumping up and down about a revolutionary new ways to mobilize collective action. Most of us have thought of it independently – I thought of it seven years ago and it’s been keeping me up at night ever since.

In simplified form this is how it goes.

If you take any political collective action you might say some people will do it and some people won’t. But in fact that is not the whole story. A lot of people will do it if they knew a lot of other people were going to do it. Before the internet came along the cost and hassle of getting to find out where other people stood was very high. With the internet people can communicate with an unlimited number of other people at effectively no cost. This, as they say, changes everything, and opens up a whole new universe of political possibility.

So let’s look at a specific situation. There’s a 1000 students on a campus. Fifty activists will go on a demo whatever – we all know the types. But as it happens 500 more people would go on the demo if they knew 500 other people would be there. It would be worth their while for whatever reasons – it might be more effective, it would be more fun and cool if that many people were there etc. So the 500 people go on a website and click on a button (ie no hassle/cost) to say they would be prepared to go on the demo if 500 people other people would also go. The target is therefore reached. The site lets everyone know (say through email) and everyone turns up. The demo attendance increases from 50 to 500 – a ten fold increase without any change in political commitments – simply by people communicating effectively with each other through the internet about what they would be prepared to do depending on what other people do.

Don’t worry about if this 500 exists or not. That’s not the point. The real undeniable point is that for every collective action there are always lots of people who would do it if they knew other people were also going to do it. There is a hidden or “latent group” which we now have the technical capacity to mobilise.

If you think this is just theoretical here’s two “little stories”:

In 2007 a website called The Point in Chicago was set up to organise political collective action through this mechanism. Proposals would be put on the site with a target of provisional support for them to go ahead. If they got to that target of support they would go ahead – if not they wouldn’t. To raise revenue they decided to organise the same collective action mechanism for local businesses. The first offer went like this: If we get 20 people to agree to go a local pizza parlour at an off peak time everyone will get a half price pizza. 20 people signed up and they all got the deal. A new company called Groupon was set up to use this mechanism in the economic sphere. Within a year 30 million Americans were using the site. Within three years it had 180 million users worldwide, was valued at $30 billion, having become the fastest growing company in the history of capitalism.

The other story is Kickstarter. Set up in 2009 it used this mechanism in for arts/culture. Again you put up a project and say how much money you need for it to go ahead. People provisionally commit money to the project and if it hits the target the project goes ahead – if not it doesn’t. By 2013 they had helped 50,000 projects get started and raised 850 millions dollars

So the question is when and how it this going to happen with radical politics? My research with Pledgebank, a UK site set up to promote the mechanism to help political projects, only half took off. The designer told me we should all be trying to work out how we can make this work for people power. My extensive data analysis of Pledgebank shows there are no fundamental blocks (I can send the research paper if you are interested). However we need to understand this mechanism in more detail and how to integrate it with the best ideas for effective action from the last 50 years. And we need to work out what to do next when it does work – how to use this mobilisation to create further mobilisation and to build a highly effective radical and participatory political movement. This is what the rest of what my research is about. I think I have almost cracked it but I need your help to work it all out in practice.

I have already done pilot research. Students were asked to email the university authorities to complain about the low pay of graduate teaching assistants. 40% said they would do so not knowing how many others would do so, but 80% said they would if they knew 500 others would do the same. As predicted people will engage in collective action much more if they know others are doing likewise – in this case a 100% more! This shows just what a dramatic effect this mechanism has. In the coming months I will be undertaking extensive field experiment to give further empirical support for the effectiveness of this method of mobilisation. This stuff is real – but we’re very much just at the beginning of working out how smart digital design can transform political mobilisation. I am an intensively practical person and if I didn’t think these mechanisms were potential dynamite I really wouldn’t be wasting your or my own time on it. (my email is organics2go@googlemail.com is you want a copy of the results)

If you are not interested stop now. If you are I need an hour or two or your time to go into the details of what this smart design entails.

Effective Political Collective Action: The Details.

Now I hope I have got your attention for a bit longer I can take things at a slower pace and set the scene in a fuller way. The first thing I want the make explicit is that ideas here do not belong to me as my possession– the issue here is not my ego. These are ideas in themselves – I am as interested as you are in working out with you what works and doesn’t work and anything that doesn’t needs to be dropped and we need to move onto other ones. Time is short, the world is in a mess, and there’s no time for egos. I come from a co-operative culture where this is clear – we are working together and it’s in this spirit that I hope to proceed.

I am also going to attempt to communicate all this in plain English. I will try to minimize academic language because I want communicate to a wide range of people. However some of the ideas need some attention to get your head around – if they were obvious they would already be out there. Where I do need to use a tricky word I hope to explain it. I’m aiming then at a middle way on this.

I am aware of course that you might be sceptical of some of these ideas – and rightly so. Ideas are cheap but as I have hopefully shown with the information about my life, I am interested in grounded ideas. I have spent my life dedicated to getting things done in the real world. I wouldn’t be messing around with these mechanisms if I didn’t genuinely believe they could have a massive impact. However at the same time we need to be very careful that, just because something doesn’t work in one situation – at one time, doesn’t not mean they won’t work ever. Making things happen involves the hard graft of constantly adapting your approach until it hits the jackpot. Here’s two stories to illustrate my point.

When I was 19 I was living in various squats in South London. I decided that squatting was all well and good but so much energy was wasted in dealing with evictions, finding new places etc. I decided that the group of unemployed activists I lived with should set up a housing co-op. I went to see the leading expert on housing co-ops in London. He told me it would impossible for a group on the dole to get hold of a property. Instead he offered me a job sorting out his archives. I thought fuck that and went and did mine own research. Six months later we had worked out how to register a co-op and get a mortgage out of a bank. Within a year we brought a large town house – got housing benefit to pay the mortgage and no more evictions. I wrote a booklet on how to set up a housing co-op which has since sold over 2000 copies – a national federation of radical housing co-ops was set up and dozens of activist groups have since used the model to get control of their housing.

When I was 25 I went to the states for a few months to research participatory decision-making in intentional communities (co-ops, communes etc) and met some people involved in community supported agriculture – selling organic veg to local people. I came back to Birmingham, where I was living, set up a workers co-op to sell organic veg from a co-op of growers in Herefordshire to people around the city. The first week’s deliveries were a disaster – everything went wrong and the two people working with me came and told me they were leaving and it couldn’t be made to work. Well you can imagine what I thought about that (see above story). I got several other people involved. We worked out how to make it work. From an initial investment of £250, we were turning over nearly a £1 million a year within four years – got a prize as the fastest growing business in the city – and had 25 people employed in the co-op.

The point of these stories is that if you have a good idea it’s not likely to work on the first outing. You have to mess around with it – have a possibly mad faith in it – and persist. Needless to say I have put other ideas into practice which have been flops. You need to know when to drop something and move on to the next idea. So with the ideas here – you need to give then a good few shots – there are lots of variations on the theme. One of them is going the fly! And that is an extremely exciting prospect.

What I am presenting here are tactical ways of being more effective, and later I will attempt to bring them together to create larger “strategic” plans of action. This does not mean I am not concerned with the content of campaigns – what is bad and why is it bad and why everyone should be doing more about it. This is what mostly gets talked about and it’s all well and good but I am talking about something else – how to change things. And to large extent the issues themselves are pretty irrelevant and I hope to persuade you that the most effective way of achieving things is not get hung up on one issue but rather to look at and choose issues we can work together on to effect change.

I also want to make clear that much of what I going to write about does not mean not doing a lot of what happens already. It’s not about dropping everything and starting a new. It’s about adding new tools and tactics onto existing ones. An analogy could be being given a bike to get from A to B rather than walking – get a gun to fight with rather than a sword. I am going to be looking at better ways, more effective “tools” to achieve our objectives.

Lastly in these introductory comments I want to make clear that in my ongoing research I am going to offer up a whole range of tactics and no one on their own is going to transform our political prospects. However in combination they are a different story. It is important to understand here what I will call the “Olympic principle”. In the last Olympics I heard a British coach discussing the exceptional UK performance. What was the key to the success he was asked. He explained that it was the accumulation of many small improvements – psychological support, diet, physical training, better kit etc. All on their own were pretty insignificant but together they pushed the athlete to the wining position. There are some important points here.

The first is that as with any race, with a political campaign there is a pretty clear difference between winning and losing – either you get something or you don’t. But to get over the line, as it were, you just need to be a tiny bit better than a situation where you do not get over the line. Small improvements make all the difference. They make can also make a massive difference in a another more complicated sense. Most political actions get lost in the enormous complexity of modern society. So many things are going on – personal, cultural, and political for everyone all the time. To get noticed you have to get win in the competition for attention. As we have identified however to get to be in this position you only have to be slightly “better” than something or someone slightly below you. And this is the important thing – once you get to this position then you start to get noticed because you are getting noticed. This is when whole thing takes off of its own accord. This has been called the “winner takes all” situation. You can see it in the media all the time. If one or two people are murdered then it doesn’t get in the news. If ten people do – only 8 people more – then it’s all over the place and everyone knows about it. So again getting that little bit better is not to be dismissed as it may be the extra tiny push we need to get to the “the tipping point” that gets the campaign to fly to its objective. My ideas here are only a framework. The real work is not in endless discussions on what will or will not work but in getting out and acquiring data on the degree of willingness of people to act in varying circumstances. Yes that means going up to people and talking to them! And as different mechanisms are deployed there will be a good possibility that they will not work. But over a number of stabs at it and, in combination with a host of other mechanisms and tactics, we are maximising our chances of getting to the tipping point where the campaign takes off and we win.

What I am going to go into some detail about here is the major focus of my attention at the present time – this “I will if you will” mechanism. However I intend to bring in several other key mechanisms, dealing with how to get your opponents to undermine themselves, and how to effectively make decisions. All these mechanisms use the the internet, mobiles etc to change to way we communicate and organise – this is the big new and open world of possibility we need to get our heads around. Used in creative combinations, I will argue they create not only a new way of campaigning but also a framework for a more deeply participatory and democratic political culture and society. I will outline scenarios which use several mechanism to maximise a campaigns chances of winning. As you will see my examples are confined to opponents which can be realistically overcome – medium sized institutions such as universities, local councils, and large companies. I am not focusing on big international issues, enormously important as they are, partly because I need to limit my focus and also because, as part of a strategy, we need to learn how to take down the smaller guys first in order to get the experience, skills, organisation, and credibility to deal with the bigger global issues. And just to make clear again, all of this I see as imitating a dialogue – at a minimum I want to try and change the focus of discussion and debate from what and why things are bad to what to do change them. Many readers will no doubt have better local knowledge than me and they will need to work out how to use these general mechanisms to fit in with these local power structures and challenges. So want I am writing here is just part of the process – the rest is over to you!

“I will if you will” and variations on the theme.

So this in the mechanism which I wish to concentrate on here. In order to fully understand it, it is necessary to get out a certain mindset that is very common. This is the idea that people do things because they want to do things – i.e. in isolation to what is happening around them and what other people are doing. Nothing could be more wrong. Although it might come as a bit of shock we are in fact massively affected by what others do and the more so the less we consciously think things through. And the vast majority of people, most of the time, just follow what other people are doing. There is limited time to think everything though. So when you might say “oh those students are not interested” what you should really be saying is those students are not interested because those students are not interested – and so you could say those students would be interested if they were interested!

So I am going to lead you through some scenarios and examples which are quite basic and then come back and answer some common objections.

With Matt Wall, a lecturer at Swansea university, we have developed three broad scenarios – which we call type 1 (T1), type 2 (T2),and type 3 (T3).

T1:

This is where we ask someone to do some collective act but they do not know or at least have no reliable or specific information about who else is doing that act. Not surprisingly, other things being equal, not many people get involved.

T2:

This is where we ask someone to do something if a certain number of other people do something. If that certain number of conditional commitments is not reached no one does anything. If it is reached then everyone agrees to act together. There are two outcomes – everyone doesn’t act or everyone does.

Note there are three lines of communication required here:

- A collective proposal is made with a target level of commitment required for it to go ahead.

- People make a conditional commitment to act on the proposal if the target of commitment is reached

- If the target is not reached no one does anything. If the target level of commitment is reached then everyone making the conditional commitment is informed and all these people act together.

So a simple example. I want to play football. I need 9 other people to turn out to make it minimally enjoyable. My proposal is – football; my target is 9 people. People make a conditional commitment to go if 9 others do the same. Two outcomes: don’t get to the target and the game doesn’t go ahead or do get to the target of 9 people and those 9 people are told it is going ahead. Pretty straightforward.

Before going onto T3 I will put this difference between T1 and T2 into a bit of context. In political theory there is something called the collective action problem. This basically deals with this issue that people want things which only make sense if a minimum number of people do them. But because no one knows if other people will do them they don’t do them either, even though if everyone did them it would make sense for all the people involved. Everyone wants to play football but not if less than 10 people show up. Because they don’t know whether 10 people will show they don’t show up themselves – hence the “problem”.

More seriously look at the issue of calling a strike. If everyone goes out on strike there the chances of getting better wages will be maximised. If everyone has to decide individually what to do and doesn’t know what other workers will do then it’s more than likely everyone will stay in work rather than risk the costs of going on strike, not knowing who else will join you. This is the T1 scenario. The T2 scenario is everyone meets in the car park. There is a vote – if over 50% vote to strike everyone goes out on strike, if less than 50% vote to go on strike then no one does so – all out or all in. This way the T2 mechanism used by the union ensures that if a strike is called its chances of success are maximised by everyone coming out. Or no one goes out and you save of costs of an ineffective strike. You get the idea. T2 does not change the individuals political commitments but through a different sort of collective organisation and communication structure transforms the political outcomes. This is the promise of T2.

The wider point here is that T2 is very difficult to organise if the costs of communication are high. There needs to be three communications – proposal, conditional commitment, and result. The history of radical activism could be summarised by dwelling on ways to get this communication to be effective between dispersed, distracted, and/or poor people. However the big recent change as we shall see is the introduction of low cost real time many to many communication which comes with the internet and social media. This new technology changes everything with regard to this problem and my research is dedicated to working out how to make best use of these new technological capacities.

I have already described the situation with The Point/Groupon and Kickstarter. The situation here is that the T2 mechanism led to an explosive growth of collective action solutions in the economic and arts/culture spheres. Briefly the collective action problem was saying I can offer a 2 for 1 pizza but only if 20 people turn up on Thursday afternoon. Make the proposal – people commit – get to the target – goes ahead. Or the collective action is I want to make a great movie but it costs a million dollars. Make the proposal – set the target – people conditionally commit. Get to the target – everyone pays knowing there’s enough money for it go ahead.

The research I have been involved in is looking a British website which, like The Point, was primarily focused on social and political collective action problems. So the idea, which should be familiar now, is that people could say “I want 100 people to go to the demonstration about x outside the local council offices”. The proposal and target is put on the website. People provisionally commit entering their email addresses. Once a time limit is up, the target is either not hit – it does not happen, or it does get hit and so goes ahead. The proposer emails all those provisionally committing to the target. My research shows that this T2 mechanism was as successfully for charitable and financial proposals as for political and off line proposals. Both local and national proposals got similar success rates. In other words there seems to be no fundamental block on T2 being used for political issues as it has been shown to be used successfully for economic and cultural collective action problems.

T3:

T3 looks complicated until you get it. T2, as described above, has been already been shown to work amazingly well in the real world. However, I believe that T3 has even greater mobilisation potential but has,as yet, not been put to the test (though I hope to get some concrete test results in the next 2 months).

With T3 the 3 stage communication goes as follows:

A proposal for a collective action is made but with no target is set.

People state the minimum number of people that would have to act for them themselves to act

If X number of people agree to act if X number of other people agree to act them the action goes head where ever X is highest.

Okay so this is complicated so let’s take a simple example. In a college there are 1000 students. A proposal is made to hold a demonstration. A 100 people will go however many others turn up. 100 will not go however many people go – they simply don’t agree with the demo. 800 people may turn up depending up how many other people turn up. We can say then that there is hidden or latent group of 800 people (1000 minus two lots of 100). How do we find out what these people would be prepared to do? By asking the following question:

If a demonstration was held what is the minimum number of people who would need to go for you also to agree to go as well?

These might be the results:

100 people agreed to go even if no one else turns up

200 people agree to go if 250 other people turn up

300 people agree to go if 350 other people turn up

400 people agree to go if 400 other people turn up

500 people agree to go if 450 other people turn up

600 people agree to go if 550 other people turn up

700 people agree to go if 700 other people turn up

800 people agree to go if 900 other people turn up

900 people agree to go if 1100 other people turn up

100 people will not turn up however many other people turn up.

What we get here then with T3 is a whole picture of the provisional commitments of the different groups of people as they become less and less committed to going to the demonstration – i.e. they need more people to turn up for them to do so as well. We can see something very interesting. First is that we can get 100 people to turn out whatever other people do. Second if we want more people to turn out we have to get the 400 people who would turn out if 400 others turn out to make a provisional commitment. But then 500 would turn out as well, as would 600, till we get to 700 where these people would turn out if a minimum of 700 others turned out (technically this should be 699 but I am trying to simplify things). After that more people will only turn out if even more people show up – something which is not going to happen. And as mentioned the last 100 people won’t show regardless of the turnout. So we can see the maximum possible turn out is 800 if everyone in the 1000 people group know each other’s threshold for participation. T3 enables us to identity this upper limit and in principle move the demonstration from 100 people attending to 700 people. Quite a difference and without any difference in people’s opinions about the demonstration – i.e. note no one has individually got any more radical/committed here. While T2 has to estimate or just guess what the maximum possible mobilisation will be and so can miss out on getting the optimal turnout, T3 enables us to identify that maximum point. While T2 says I will if you will, T3 asks what is the minimum number you need to do x for you to do it as well. With this open question you get a complete picture of the political collective action situation.

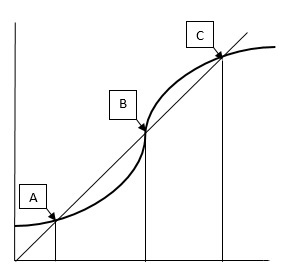

So I am going to do a diagram which will help you appreciate the revolutionary potential of T2 and T3.

For the sake of argument I assume all collective action problems have the same structure. Basically they will go ahead if X number of people know that (X-1) other people will also act.

So here is the graph that shows this situation.

|

Any point on the S curve shows how many other people will need to act in order for the number of the horizontal axis also to act. Some people will engage in the collective act regardless of what others do. These are the altruists – up to point A, while others will not act however many other people act. The key group are the people who will take action but only if a minimum number of others do so as well. On the above graph then the collective action becomes attractive again only at point B where the S curve again crosses the diagonal. This ‘crossing the chasm’ (from point A to point B) challenge requires an overcoming of “pluralistic ignorance” where everyone in the group does not know where each other’s minimum ‘taking action point’ is. However through T3 data collection this graph becomes available for all members of the latent group. Where the S curve crosses the diagonal for a second time (point B) there is a higher and much more effective level of collective action and the “latent group” can become active. What’s more the T3 data shows the maximum number prepared to take part (where the S curve crosses the diagonal for the third time at point C). This point then gives the objective maximum level of achievable collective action.

All this is of course quite theoretical but let me give you an example which shows that what we are talking about here is highly relevant to political practice – indeed it can be a life and death matter. Some collective action problems are not trivial. A classic example is the dictator problem. No one supports the dictator but no one is going to protest unless everyone else does on because they will get shot, so no one protests so the dictator stays in power. Now let’s look at what happened with the 2011 Egyptian revolution. This again is a simplified story of the events and it might not be true in every detail (as with all these things there’s lots of debate) but here it is. There was a Facebook page on which the first demonstration was called for the 25th January. Over 80,000 people pre-committed on the page to turn up. All these 80,000 people could see that 80,000 other people were also committed. When the demonstration was held these people had the courage to show up and thousands of others joined them once they saw there was a critical mass of people on the street. They broke through the “fear barrier” – that is they knew that while it was still risky it was now worth taking that risk to join a protest to bring down the regime they hated. Once the demonstration happened the flood gates opened and within two weeks three million were on the streets and on February 9th Mubarak, the dictator, stood down. Of course this is not the whole story but you can see how the above graph clearly shows how this part of the story happened. The “chasm” from point A to point B was crossed because of the pre commitments on Faceook and then everything exploded up to point C.

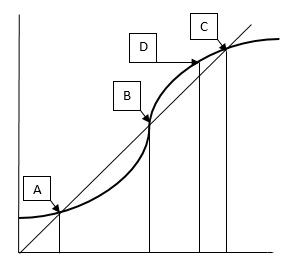

We can also put in a line here which represents the level of mobilisation needed to win in a straight forward win lose situation – like the dictator stays in power versus he falls from power. We could say this winning point which brings down the regime is point D.

|

So in summary then, if people do not know what others are prepared to do you will only get turnout to point A. If you use a T3 mechanism you can get this same group of people to mobilise up to point C. And critically if you get past point D you have brought enough pressure to bear to win whatever collective action you engage it. Cross point D and you have won.

I should say at this point that not all collective activity has this “crossing the chasm” between point A and point B problem. For instance a lot of thing people do collective activities which are not affected by other people. For instance a lot of people take their dog for a walk in the park. And in the normal course of things the number of other people doing it is neither here nor there. There is another category of collective action which is so costly that, even if everyone acted together it, would still not work. So for instance a lot of people would like to go travelling to another galaxy. It’s not possible to do it alone, but even if everyone worked together on it, it still won’t make sense because the costs would still be too great.

So our collective action problem then is a special case. And collective action problems which have the winning point D between points B and C are the scenarios where the prize of success is totally achievable through a T3 mechanism.

I will develop this theory in one more direction and then look at some of practical issues and problems. One of the iron laws of political participation is that some people are more committed than others. To be more precise there are always some people who are really committed, some who are pretty committed and so on down to people who are sort of, but don’t do anything etc. I think if you plotted this on a chart you would get some variation on following curve.

|

The basic shape is of this “power law” curve is as follows. There is a “vertical tail” where the line stretches up against the vertical axis, and then the tail changes direction and stretches out along the horizontal axis. A real world example which produces this sort of curve is book sales. A few books sell millions of copies (vertical tail) and then millions of other books just sell a few copies (horizontal tail). In power law curves there are these two “long tails”.

So with a campaign you get very few people willing to do a very high risk/costly action (vertical tail) and lots of people willing to do a very low risk/cost activity. A typical situation is that you might have 4 people willing to do an occupation, 10 willing to organise a campaign, 50 people willing to collect signatures and 500 people willing to sign one. So you can see what is coming. This is the state of play when no one knows what anyone else is prepared to do. Using the T3 mechanism allows each of these groups to overcome their own only collective action problem. Maybe 20 people would be willing to do an occupation if another 19 would also commit to it. Maybe 150 people would get involved in organising the campaign if they know 150 others would also be involved. Maybe 200 people would help organise a petition if around 200 others were also involved. And maybe 5000 people would sign the petition if they knew another 5000 people would also be up for it.

You can play around with the figures but hopefully you get the idea. Again this is not about persuading others to be more committed/radical – it’s purely about people knowing what others would be willing to do and committing on the condition that a minimum number of others are also committed to the same activity.

There two things happening here I want to flag up.

First is that what happens at the extremes of each tail as the “volume” of the whole distribution under the curve increases. Something happens which we naturally have a big problem getting our heads around – what is called a “cognitive error”. We tend the think of numbers going up in a straight “linear” line like 2 4 6 8 rather than by a “power” like 1 4 9 16 25 (that is 1×1, 2×2, 3×3 etc). This means it’s really easy to underestimate what will happens to the extremes as the whole distribution expands. The end point on the horizontal axis might expand from 100 to 10000 rather than say 500 as we might incorrectly expect. And the same on the vertical axis. What this means in political terms is that a small group of people who before might just do a high cost occupation might now do something very much more costly like go on hunger strike. While on the horizontal axis you might find that while 1000 people would sign a petition, now 50,000 people would. This might seem unbelievable but this is what the maths predicts.

Secondly you have more commitment right across the board from very high risk/cost to very low risk/cost. This gives a hint of why, in the context of political activism, the mathematical prediction just mentioned is correct. You can easily see a feedback and compounding effect happening. The very high cost activity inspires the organising activists who in turn get more signatures for the petition – and as more people get to know about the success of the petition many more are happy to sign it.

This T3 application at each stage of the commitment curve then gives a more complete picture compared the previous simple one activity model of whether to go on a demo. In a more complex real world situation we are more likely to envisage a combination of a few high risk activities and a large amount of low risk activities. The point is that in this model they all combine to push the total strength of the campaign over that line (point D) where the opponent chooses to negotiate or give in rather than hold out. If we reduce this to numbers you might have the following situation:

Before T3:

2 people on high cost, effect of 10 =20

10 people medium cost, effect of 5 = 50

100 people low cost, effect of 1= 100

Total force/effect = 100+50+20= 170

After T3:

5 people at very high cost, effect of 50 = 250

200 people at medium cost, effect of 5 = 400

2000 people at low cost, effect of 1= 2000

Total cost force/effect = 250+400+2000= 2650

It the force/effect needed is below 2650 but above 170 – say at 2000 then T3 will have been the critical mechanism to take the campaign over the line.

T3 then is applicable to all levels of commitment as the same collective action problem occurs a stages all along the line. The cumulative effect of boosting force/effect at all levels on the power law curve of political action maximises the chances of success.

Problems and Practicalities.

So much for the theory. Having talked to quite a few people about this now some people just don’t get it at all (often, even if something makes sense on paper people don’t believe it till they see it), some people do , and a third group understand its power but raise two important problems which I will deal with here.

Free riding.

So what is to stop people saying they will do something with others but for whatever reason (rational calculation, just forgetting, mental problems, whatever) don’t carry through on their commitment to act with others when they are informed that the collective threshold has been reached at which they have agreed to act. Well here we have to return to the real world of messy empirical evidence. First of all we have to realise just because a theory says something should or should not happen does not mean that reality follows the theory. Reality comes first and theory second. What I am getting at here is that there is a certain approach to these matters, which we don’t need to get bogged down too much in, which to says that everyone follows their “self interest”. This idea has a lot going for it but not if you take it to extremes. So as I hope to show some people think “rationally” in terms of their self interest about collective action problems. I will not do X unless Y people do it as well – otherwise the costs to me are too high. However empirically very few people will go hey Y people are now doing X on the agreement that they and I all work together so I will now not do X, knowing that Y people will get X for me without me showing up. That is to say people do not in general cheat. But at the end of the day this is a straight forward empirical question and then a question of design.

So the empirical evidence. Pledgebank asked initiators of proposals that had successfully got to their target of support on their website to report how many people actually fulfilled their pledge. The answer was 75-150%. I will deal with the 150% issue in a minute. But the point is that while “free riding” can happen it is not critical – ie only getting 75% it is not terrible particularly as we can assume that most pledges will have got effectively 100% of people to come true on their pledge.

There are several other comments that can be plausibly be made here.

Firstly in small groups, where people know each other, it is reasonable to assume that people will care about their reputation and this will be adversely effected by cheating on their commitments. With social media it is possible this reputation constraint can apply to larger groups – a design challenge for T3 experimentation.

On financial matters, as designed in by Groupon and Kickstarter, there in no way you can get out of your provisional commitment if the target is reached. You pay by credit card and the money is already taken out of your account and is only refunded if the target is not reached. Neat!

Most people will not consciously cheat on an ethical matter which they are in principle committed to. But it is possible many may fail to act if the action is small and they may simply forget because of the pressure of other matters calling for their attention. Therefore a key design element is to have a short time span between the making of a provisional commitment and a calling on that commitment.

At the end of the day then this is an empirical matter – it will come out in the wash – in the testing of T2 and T3 mechanisms in a variety of contexts. But what I hope is clear is that while this problem does exist it does not critically undermine the success of these mechanisms. We could also say that as and when these mechanisms become more common people will fulfil their commitments more consistently in the same way as people do not generally cheat in when engaging in established modes of volunteer collective activity.

There is another more positive side to this acting on commitments issue. And that is that people will join the collective action after it hits the target. Having got to its target it creates wider effects and can start a self-perpetuating upward spiral of support. Let’s take an example of a letter writing campaign. Lets say that 300 people will write a letter regardless of how many other do it (T1). Organisers find 800 people who will do it if 800 others also do it (T3). The target is reached everyone gets an email to send their letter. Let say 600 do it and 200 don’t bother. However 200 of that 600 who do do it might, particularly if prompted, get excited by the idea of being part of 800 people committed to writing a letter- even more so if objectively this might win a campaign. So via social media they will tell their friends who will tell their’s, saying something like – “did you know 800 people are writing this letter – why don’t you do it as well”. So we could envisage a situation where 200 people dropped out but another 400 joined though “viral effects” making a total of 1200 letters sent – more than the original target. My research on Pledgebank shows that while the vast majority of successful pledges involved less than 500 people there was a long tail of outlier proposals that attracted way more support than their target, stretching up to 11,000 pledges for one proposal.

Getting attention and getting it going.

This I think is the biggest problem. There are in fact several problems here.

First this is new and most people most of the time can’t get their heads round new things even if they make sense. That said T2/T3 is not rocket science. Seat down for around 5 minutes with a reasonably open person and they should get the idea.

But this leads onto the other problem- how to get this attention. Modern society more than ever before has a literally a million and one things demanding our attention all the time. How do we get attention in all this “noise”. To put it bluntly this is the problem: there are 5 of you sitting in a room wanting to run a successful campaign and there are thousands of people out there, in principle, in support of it but they have a hundred and one other things to keep them occupied – personal lives, work, online distractions etc. You might set up a website which is great and have a just cause but you are unlikely to get attention in all this noise.

This is the thing they don’t tell you in those change the world books. They will give you a scenario which is already successful – “the way to do it is to get 100,000 people to march on parliament” – This describes the success not the way to get to the success. How to you get 100 000 to march on parliament? The start up process is in fact very different to what you might call the up and going steady state campaign process which I have described above. Specifically how do we get 500 people to say that they will act if 500 other people will also act. They may well all act but the real problem is how to get their attention for them to realise this. An analogy is that we might all now know about how to walk to the beach but if we are starting from being stuck in a hole what we need to know is how to get out of the hole first. Without this knowledge, however much we know about the walking to the beach part, nothing is going to happen. It’s like the first baby collective action problem.

This is how I suggest you do it. In a limited space like a university or local authority you need to get off line and go and speak to people in this space to kickstart the progress. You can also talk to groups, or identify key networking people in the large group you want to mobilise. There are various ways to do it and I am going to get very specific here because this is a very much a here and now immediate problem. What follows is not “the only way” and no doubt the various micro mechanisms which can be tweeked and re combined for better effect. This is a matter of trial and error but it gives, I hope, a clear way of getting out of the hole, to get heard in the noise, and get to walk to the beach.

The example I will give relates, as of march 2015, to an experiment I am hoping shortly to conduct which will show concrete real world evidence (or not!) of the power of T2/T3 mechanisms. I have not totally refined the process and am presently doing few pilot tests to improve the design but this is the general plan so far. Once I have outlined it I will give various tips on why it will work and how to maximise it mobilisation potential.

The topic I have chosen is the issue the pay of graduate teaching assistants (GTAs). Often the pay is just for the teaching hour and not for the prep work and so the pay can be as little as £4 an hour if all the necessary work is included.

The collective action proposal will be for people to write a personal 1-2 paragraph letter to the Vice Chancellor to ask that GTA’s get the London minimum wage for each hour of work they have to do to do the job properly.

So for the purposes of my research I would have one group (control) that is just asked to do this without any reference to what anyone else does. For a larger group (treatment) I would go up to people sitting in university cafes etc and ask I could go through a questionnaire for my research with them.

This in draft form is the questionnaire;

Questionnaire for treatment group

Would you support our campaign to make sure all PhD students teaching other students at Kings receive at least the minimum the London living wage (£9.15/hour) for their work teaching other students. Please tick

Yes…

No …

If yes please answer the following question…We are organising a mass emailing of the Vice Chancellor to support our campaign. We are asking people to email the VC a short letter which briefly explains why you support the campaign. The more people to do this the more likely we will get a living wages for PhD teachers

So please tick by the Yes or No for the following questions

If 5,000 people were prepared to send an email would you would be prepared to send an email yourself as well.

Tick

Yes

No

If 1000 people were prepared to send an email would you would be prepared to send an email yourself as well.

Tick

Yes

No

If 500 people were prepared to send an email would you would be prepared to send an email yourself as well.

Tick

Yes

No

If 100 people were prepared to send an email would you would be prepared to send an email yourself as well.

Tick

Yes

No

Would you be prepared to email a letter regardless of how many other people did the same

Tick

Yes

No.

If you have said yes to any of the above possibilities please can you write your email address below and we will email you in the next week if we have enough people prepared to act with you to start the emailing campaign.. Thanks for your support.

Email address – Please write clearly in BLOCK CAPITALS.

I am now going to make a few assumptions which may or may not be true but enable me to show how the campaign gets to take off.

Firstly let’s say after speaking to a 100 people you get 70 (my pilot gave 80%) you would write a letter if 500 or more other people would write a letter. You immediately now have enough information to get out of the hole. This is how it goes.

To get to your 500 people writing an email target you now know you have to speak to 1000 people – (50 out of 100 do it so 500 out of 1000 will). I have done extensive canvassing and a trained/talented canvasser could see 30 people an hour – 1 every 1.5 minutes – bearing in mind if you go to a table you can get up to 5 people to respond at once. I ran an online business at Swansea university and me and a fellow canvasser talked to people at uni cafes and got 50 emails/yes’s an hour, so it can be done. So let’s assume a canvasser can see 30 people an hour, that’s 20 commitments an hour. So that is 50 hours of canvassing to get to our 1000 commitments . So your five people in the room get out and do 10 hours of canvassing each, say, over four days (2.5 hours each a day – over lunch times in university cafes).

So suddenly in four days you have 500 people who will act for you and 500 email addresses.

In this scenario you then email the 500 people with details on how to write the letter, giving them lots of facts and figures to choose from, and ask them send the email to you as well as sending it onto to V.C.

You now have in principle an audience (ie emails) of 500 supporters and crucially, through social media, these supporters will attract even more people to your cause.

Analysis and considerations.

Before finishing there are number of points to be made about this example.

First of all I am not making any claims about how good or bad this issue is nor whether getting 500 people to write an email to the VC will win a campaign. It is simply to show you how talking directly to people to gets us out of the hole – the initial start up problem of a campaign. And in terms of the effectiveness of T2/T3 it will show how much more effectively these mechanisms are compared with the control group where people are not told what other people might do.

Given that people reading this may want to follow this method I want to spend a little time pointing out important micro design elements which might critically enhance the effectiveness of this procedure. As already mentioned small changes – additions and omissions – can make all the difference in the success or failure of a technique. So here are some pointers.

1.. You need to get people relaxing – sitting down in a café, standing up waiting for something, in their accommodation are the main three situations. That is, not when they are physically moving – it is difficult to keep up with them and speak! And if they’re working they don’t want to be disturbed.

2.. You have to sound confident and/or authentic and come across as likeable. This comes from practice but it helps if you know how important it is. This is particularly important in the first few seconds of contact. It is always best to apologise in the opening line – “Hi sorry about disturbing you but I was just wondering if a could ask you a few questions about some research I am doing – it will only take a minute – (they say ok) – oh thanks (sit down and off you go).

- The above questionnaire as we have discussed uses a T3 framework – how many people would have to do X for you to do this as well. It does have a T2 prompt –ie it gives you an example of a target to ground the question. (At this stage I intuit that is best approach – but research results could come up with a better construction). We have already discussed why this overcomes the collective action problem. But there is another psychological mechanism going on here. Once a person says yes to doing it if 10 000 others do so (and who wouldn’t might be the subtext) then the person is more likely to answer yes to 1 000 then if you started with the 1 000 question. This is because he/she has already said yes once. Psychologically it is easier to carry on with yes than to change to no.

- Once you have gone through the question and if they have said yes to one or more of the T3 scenarios you can then ask for their email address. Although in normal circumstances people do not give their email out for obvious reasons you will find that through the process of interaction and the positive responses they have given you they are likely to give the email addresses in 95% of cases (based upon the data from my canvassing in Swansea). As we will see below this is a crucial resource.

So much for the micro design. The next step is to look more closely at the follow up process. There are various ways of getting them to send the email. The aim is to maximise the conversion rate from commitment to action. As discussed above with the data from Pledgebank it is likely there will be a drop off rate but not an overly significant one. Again there are various micro techniques to ensure that the drop is minimised. You can state that 500 other people are now sending out their letter (subtext others are fulfilling their commitment /I am part of a group – so I should/will do it too). Incidentally the government has used this “social information” to get more people to pay their tax on time – I think the line is “95% if people have now paid their taxes” – the mere statement of the fact gives power to the request for them to do so as well. There can be a follow up email to them like this – “80% of people have now fulfilled their agreement to send an email to the VC..”

An additional approach is to personalise the communication. When doing the survey mention your name. Give them a leaflet after getting the email giving them more information about yourself. Send a follow up email “Hi this is John. I spoke to you today…” to confirm the provisional commitment. Then personalise the action request – so it creates the idea that they are fulfilling a commitment to a real person they know rather than to an impersonal campaign.

As mentioned above, while the empirical evidence shows that there will be a fall off, it is also very likely, particularly if encouraged, for there to be a increase in total actions taken because of the effect of enthusiasts amongst our 500 people communicating via social media to friends and contacts about this campaign of writing to the VC. This can be enhanced by the following mechanisms.

1.. Once a person has been given their email they are given a leaflet detailing all the information and asked to pass the information onto friends – it will have a website address on the leaflet where people can fill in the questionnaire on line with a real time total of the number of commitment given and how many more are needed for the 500 target for the go ahead. Note that, drawing on the data from Kickstarter and Pledgebank, once proposal gets to 20-40% of the support it needs to get to its target, word of mouth kicks in and this propels the targets to get to their target. Often this momentum pushes past the target as the enthusiasm via social media creates a viral effect. Lots of people tell lots of people and action undertaken increases at an ever increasing i.e. exponential rate. Once the 500 people target is met we can email these people- put on the website the new target of getting 1000 people. We can say something like – “heys guys got 500 let’s get to 1000 – tell your friends”

- Once you have the email within a few hours they should be emailed to confirm they have made the commitment and again be given all the information to encourage them to get their friends on board with links to articles about the cause and to the website.

- If someone is extra enthusiastic and/or outraged by the injustice, you can star their email and ask them to come to the next meeting and/or send them a tailored email giving them options on how to get more involves and several dates when they can come to a meeting.

The general point here is that the seeing people face to face is the kickstarter mechanism which is then enhanced by online/social media amplification. It gives valuable information about the level of commitment of the political group you are trying to mobilised – how radical it is – and how steep the “curve” of political commitment is – from potential activists through to people who are mildly committed. For instance if you speak to 100 people and 5 say they want to be involved in the campaign then if there are 5000 students you know there are 250 potential activists out there to get on board (5% of 5000). This information is invaluable for a campaign as it enables you know your potential maximum resources.

Concluding comments

Over the coming months I hope to produce concrete and numerical evidence of how much more effective T3 is over T1. My hunch is it could be three times –time will tell. What I hope to have convinced you of is that simply by doing things differently with the resources you have (we are not being idealistic here and dreaming we have more than we actually have) you can significantly and potentially massively increase mobilisation. Of course this does not guarantee that this enhanced mobilisation will get you over the line and allow you to win a campaign but it will make it much more likely.

Through my research and effective data collection by any campaigns using these techniques I hope, through trial and error, to tweek these mechanisms to maximize their effectiveness.

A quick word to any academics (or academically minded readers). As you will have noticed if you know about this field I have avoided a lot of the lingo and theoretical phrasing which you find in the academic literature. A lot of what I have to say has its grounding in game theory, network theory and behavioural psychology/economics. And of course there are a number of interesting issues all this raises –rational versus socialised action to name but one. I am of course very interested in all this but my focus here in wanting to connect with real world groups here and now in London. But please do contact me if you want to see papers I have written for journals on the issue.

For everyone reading this – thanks for your time. I guess if you are reading it you are the sort of person who is open to new ideas and approaches to what we no doubt all know is a massively important issue – how do we create bottom up radical political change.

To re emphase what I have written here is just the beginning. By interacting and entering into dialogue with people like you I hope together we can make these ideas fly. Also what is written here is just one part of whole range of mobilisation and organisation mechanisms I am working on and want to communicate. Taking the Olympic winning strategy analogy , T3 is just one part of the mix. It needs to the integrated with various other smart techniques to maximise the possibility of winning a campaign and more generally, and no less crucially in the longer term, to create the organisational structures which create radical democratic culture and political power. This after all is the general project is it not?

On this matter I hope to produce documentation outlining two other broader mechanisms which I think as just as important as T3. I will briefly outline them here – to give you a taste of what is to come:

Dilemma actions:

Raising mobilisation is one thing but as the data will possibly show even with T3 enhancement there may not be the political resources in the whole political group to get to the winning position. However often situations can be created from the existing mobilisation, or come from the opponent in response to this existing mobilisation, which create an event which significantly increases the potential resources available for the campaign. A simple example; the university get hundreds of emails and phone calls from T3 mobilised students. It over reacts and suspends some students for organising the T3 action. This creates outrage amongst normally apathetic students and many more start blocking up the university communication channels. The winning point is then reached – the university backs down agrees to the demand and the suspensions are lifted. This is a simple example which may or may not be realistic but this process is the key mechanism in the winning of so many historical campaigns. Authorities know this –hence the aim to create a dilemma for them – not react and be subject to raising costs – crackdown but risk provoking even greater mobilisation.

Sortition/Mini publics:

How do you organise a campaign, negotiate to end the campaign- and generally make collective decisions? The conventional dilemma is mass participatory but ineffective decision making (horzontalism) versus having a top down group/person calling the shots which may be effective but is alienating and contradicts the ideas of a radical political culture etc. The solution I propose is sorition or mini publics. Here a small group of people who are representative of the whole group are picked by chance (so no power manipulations) to be the decision makers/ negotiators. The advantage is a small group is it is manageable and can be effective and make quick decisions AND, it has legitimacy because it is transparently selected by lot – ie representative of the make up of the whole political group. There is a lot to be said about this ancient form of democracy (first used in Athens) and I think it has massive potential when enhanced by digital technology.

I will be writing up the initial cases for these frameworks in the coming weeks. If you are interested in receiving these texts please contact me on the email below.

But back to now. I am extremely interested in working with groups and/or individuals in groups, and/or researchers who want to see T3 get some real world exposure. I envisage that this piece of writing will lead to me talking to some individuals. The next step I am angling for is to do presentations for groups of activists and then to work will them to integrate T3 into their campaigns. Alternatively I am interested in working with other researchers/interested students in doing field experiments to test the effectiveness of T3. In the longer term I have the idea of setting up a research group, which could evolve into a think tank, which aims to discover, crowd source and disseminate the cutting edge techniques, processes etc which make bottom up democracy and radical campaigning work. With the rise of digital technologies and the increasing alienation from conventional political forms, I think we are entering a time of great radical political creativity.

So please contact and we can meet. Thanks so much for taking the time to read all this and the best of luck in any campaigning you are doing (enhanced by smart thinking!)

Roger Hallam

Email: organics2go@googlemail.com.

[…] Conditional Commitment – If you want to do an action that requires a certain amount of people to make a splash, then conditional commitment is an effective way to get the numbers. In the UK The UCL Rent Strike has made a massive impact. 120 students went on strike against cost and conditions of accommodation and successfully forced UCL to pay compensation. A critical factor in this action was the fact that people weren’t asked “will you go on strike”, which only had a 50% agreement, they instead asked “would you go on strike if 100 people will”, when this approach was used 78% of people agreed and the action was able to get enough people to go ahead. This is a really simple detail, but it is the difference between success and failure and shows why campaigning need to be intelligently and strategically designed. See here for more info on conditional commitment. […]

LikeLike

[…] Hallam’s concept of “Conditional Commitment” involves assuring potential strikers that a strike will only go ahead once a certain number of […]

LikeLike

[…] more information on conditional commitment check out: https://radicalthinktank.wordpress.com/2015/11/01/introduction-to-the-design-of-effective-political-… (on the RTT […]

LikeLike

[…] Hallam’s concept of “Conditional Commitment” involves assuring potential strikers that a strike will only go ahead once a certain number of […]

LikeLike